Modern technology and safety procedures have drastically reduced maritime accidents over the last 100 years, but shipping disasters can still occur. Here’s a look at some of the most notable maritime disasters – and how to protect your cargo against future accidents.

Maritime Disasters from 1840-1920

SS North Carolina (1840)

A luxury steamliner built for elite passengers and their cargo, the SS North Carolina was about 20 miles off the South Carolina coast when its sister ship, the Governor Dudley, split the vessel in two. Among the passengers were 13 congressmen – and all their savings in newly-minted gold coins. Within minutes, the North Carolina sank, sending passengers to flee to lifeboats and board the Dudley, many without time to even fill their pockets with belongings.

It’s estimated that tens of millions of dollars worth of rare gold coins were lost in the wreckage, which was only located in the late 1990s – and only part of the treasure has been recovered.

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror (1845)

Known as Franklin’s lost expedition, the story of the loss of both ships and their 129 combined crew has become folklore, with stories of abandonment, starvation, cannibalism, and even a modern story about paranoia and hallucinations haunting the doomed mission through the Arctic.

Intended to discover a northwest trade passage through the Arctic, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were among the most technologically advanced ships in the world, outfitted with iron plating and retrofitted with steam engines. Besides the loss of the crew, both ships were lost for over a century and all supplies, cargo, and valuables aboard were lost. While clues to the fate of the crew were found throughout the years, it wasn’t until 2014 and 2016 that the Erebus and Terror, respectively, were found.

SS Central America (1857)

The worst non-wartime wreckage in American history, the SS Central America was a steamliner carrying ⅕ of all gold in Wall Street Banks from the California Gold Rush before it sank off the United States’ east coast.

Departing from Panama and headed to New York City, the trip was uneventful before it began taking heavy water and endured 105 MPH winds, causing the ship’s sails to break and its steam engine to fail. By the time help arrived, only 153 passengers had survived and 425 people were killed. It’s estimated that over 9 tons of gold valued at $8 million ($550 million in 2019 value) was lost, which resulted in the Panic of 1857 and a general loss of confidence in the United States economy.

RMS Atlantic (1873)

The historic White Star Line’s most famous accident at sea is not a surprise – after all, everyone knows about the fate of the RMS Titanic – but 30 years prior, another disaster stunned the company. The RMS Atlantic, carrying goods, cargo, and nearly 1,000 passengers and crew, made way from Queenstown, Ireland to New York in March 1873. A few days into the journey, the ship encountered heavy winds and strong gales, slowing their progress and forcing them to burn through more coal than anticipated.

Captain James A. Williams, who some historians blame for the disaster, instructed the crew to proceed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to secure more coal before continuing to New York.

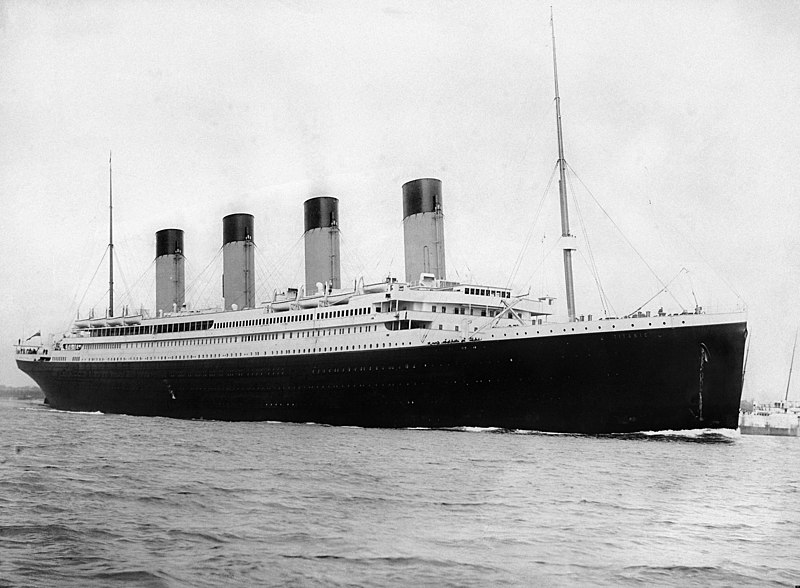

RMS Titanic (1912)

Arguably the most famous maritime disaster in history, the luxury liner was the largest ship of its time. Well marketed and widely publicized, the ship was designed with the comforts of modern life in mind with a (relatively) small focus on transporting cargo. Nevertheless, the legendary ship was meant to compete with White Star Line’s primary opposition, Cucard Line, which had just rolled out the Lusitania and the Mauritania – and offered record-breaking speed across the Atlantic.

Built in Belfast, Ireland, in a new shipyard that had to be specially constructed by shipbuilders Harland and Wolff, the sheer size of the vessel posed major engineering problems. Not only would the Titanic be the largest passenger ship ever constructed, it was meant to be the most technologically advanced, efficient, and luxurious. And due to the cost of each ship of White Star Line’s new Olympic fleet, Titanic and its sister ship, Olympic, were built simultaneously.

Of course, everyone knows the story of the Titanic and the tragedy that ensued, but it was a true turning point in the downfall of White Star Line’s reign in the Atlantic and informed shipbuilding design, safety capabilities, and operational standards for decades to come.

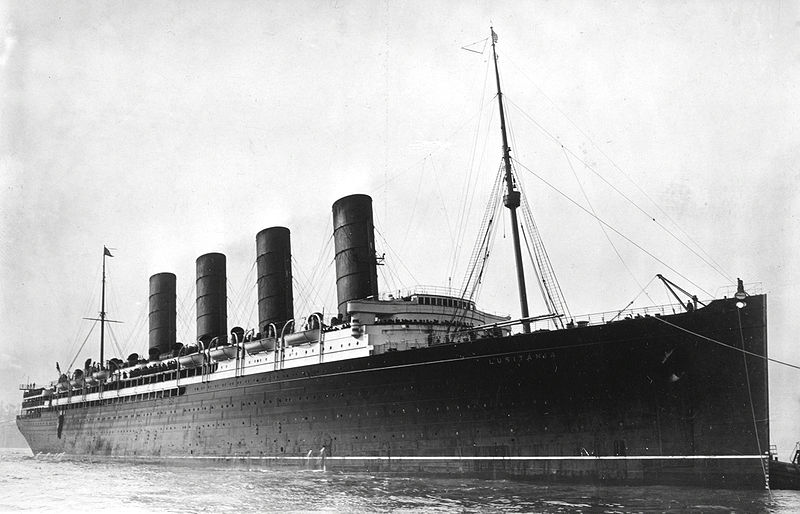

RMS Lusitania (1915)

Arguably one of the major turning points for the United States joining the war against Germany in World War 1, the sinking of British ocean liner RMS Lusitania was a devastating and horrifying event in the lead up to U.S. involvement in the war effort. Despite the ship’s history of transporting munitions and supplies to the British war effort, its final journey included mostly passengers – including 128 Americans – which helps sway public opinion toward joining the war effort.

Departing from New York to Liverpool, the Lusitania was off the coast of Ireland on May 7th, 1915, when it crossed paths with a German U-boat, which opened fire and struck the Lusitania’s starboard bow with a torpedo. A second explosion occurred in the aftermath of the first attack, bringing the ship to its knees. Nearly 1,200 of the 1,962 passengers perished and only six lifeboats were deployed in time.

SS Mont-Blanc (1917)

Remarkable for many reasons, the Mont-Blanc disaster actually occurred at port. Laden with high explosives, the ship was struck by the SS Imo in the upper Halifax Harbour, igniting damaged benzol barrels onboard, and exploded in the Richmond district of the city, killing 2,000 people and injuring 9,000 others.

The ship carried nearly 3,000 tons of explosives that were intended to resupply Allied efforts during World War 1 in Europe, but missed its convoy from New York and rerouted to Halifax in an effort to join a new journey across the Atlantic. The Imo was ready to go, but due to heavy traffic through the port, the queue to depart kept them in harbor for several extra days. Frustrated, the Imo’s captain launched without permission, encountering the Mont-Blanc in the harbor and refused to give way to the oncoming ship. The resulting blast was, at the time, the largest man-made explosion in human history.

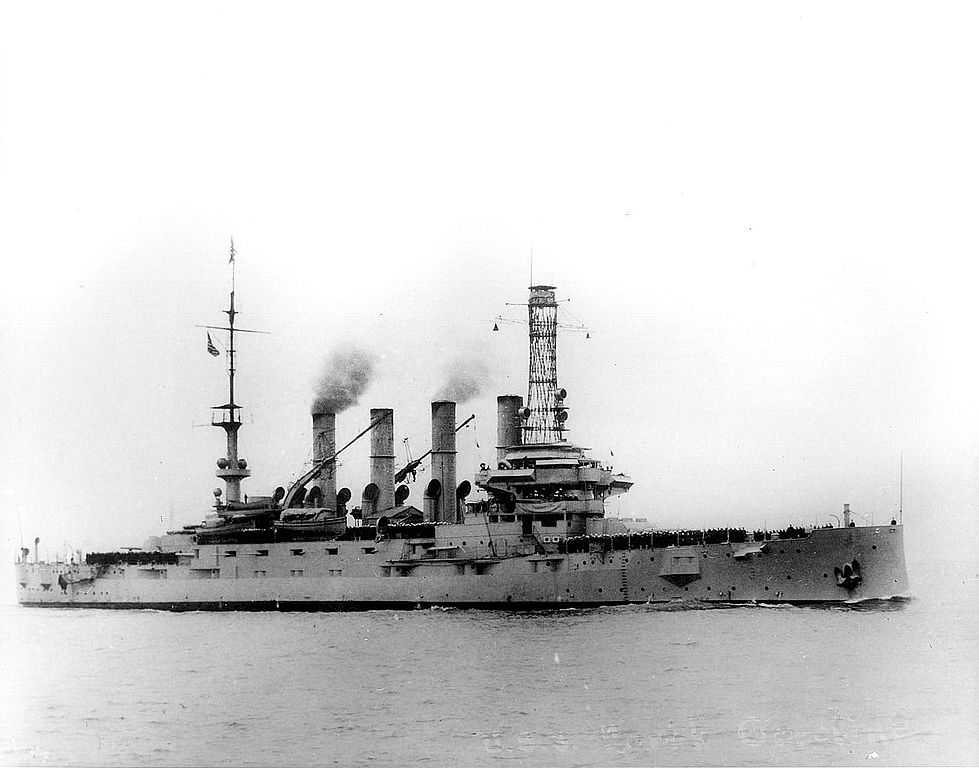

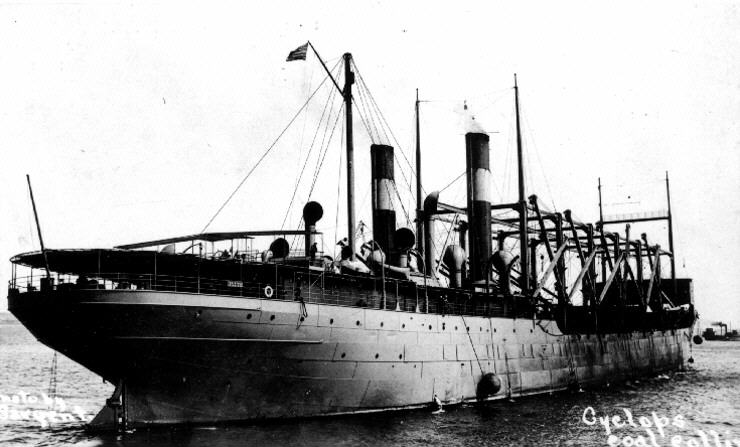

USS Cyclops (1918)

A major provider of coal, gasoline, and other vital materials for the United States Navy, the USS Cyclops set out from Rio de Janeiro to Baltimore with a reportedly overloaded hull, causing the ship to dip below the Plimsoll line. Several reported sightings were considered in the final report on the ship, which was overseen by then Undersecretary of the Navy and future president, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The Cyclops was carrying approximately 10,800 long tons of manganese ore among other munitions materials when it disappeared in the region known as the Bermuda Triangle. Despite reports that it may have been sunk by a German raider or submarine, the most plausible cause of its sinking is an encounter with an unexpected storm, resulting in a total loss of the vessel and the 306 crew and passengers, which have never been recovered.

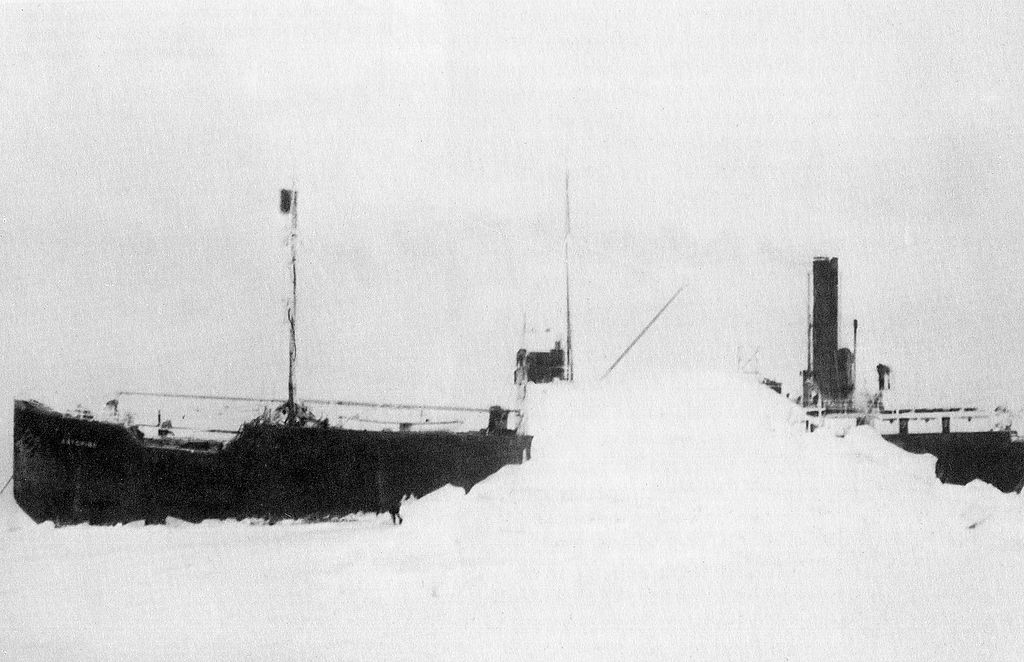

SS Baychimo (1931)

Originally built for the German Empire in 1914, the Baychimo was a 1,322 ton cargo ship used during World War I to transport goods between Hamburg, Germany and Sweden. Once the war was over, the ship became a part of German reparations and transferred to the United Kingdom before its acquisition by the Hudson Bay Company in 1921.

In 1931, the ship became trapped in pack ice at the end of a trading run on its way to Alaska, forcing the crew to abandon ship and take refuge in a nearby town. But storms continued to hound the ship and within a month, there was no sign of the vessel. Laden down with furs and other goods, the crew assumed the ship had sunk in place or broken up during the storm, but mysteriously, there have been reports of Baychimo several times – including one almost 40 years later in 1969, but there’s no clear cut determination as to its fate.

MV Doña Paz/MT Vector (1987)

In December 1987, a passenger ferry in the Philippines carried over 2,000 people above the manifest’s official tally overnight from Leyte Island to Manila when it collided with an oil tanker.

The MV Doña Paz, a 93 meter-long ferry with a capacity of 1,518 passengers, was reportedly a victim of illegal ticketing, putting the estimated passenger count between 3,000-4,000 people during a busy holiday season. While passengers slept, the vessel violently collided with MT Vector, a tanker with over 1,000 metric tons of gasoline and petroleum products onboard. The Vector’s cargo ignited, spreading fire to the MV Doña Paz and the surrounding waters. To make matters worse, the lockers that contained life jackets aboard the MV Doña Paz were locked, forcing passengers to leap from the rapidly sinking ship and into shark-infested waters. After an hour, a passing ship located survivors and ultimately rescued only 26 people from both ships.

Marine Disasters from 2000-2019

MOL Comfort (2013)

One of the largest and most catastrophic cargo losses in history, the MOL Comfort, built just 5 years prior, developed a crack at midship and broke in half. While the cause of the break remains unknown, the disaster resulted in a loss of more than 2,400 containers, $300-400 million in insurance claims, and over 100 lawsuits against the shipbuilder.

SS El Faro (2015)

Arguably the worst cargo ship disaster in modern history, El Faro carried nearly 400 shipping containers, 300 trailers and cars, and 33 crew members from Jacksonville, Florida on September 29, 2015 to its intended destination of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Hurricane Joaquin had other ideas.

While Captain Michael Davidson altered the ship’s course to avoid the then tropical storm, Joaquin intensified into a Category 3 hurricane and El Faro, bizarrely, deviated from its course directly into the storm. This alarmed the crew, some of whom called the 40-year old ship “a rust bucket that was not supposed to be on the water.”

But the biggest blunder may not have been the seaworthiness of the ship, but its lack of standard safety features and procedures. El Faro began to take water almost immediately after encountering Joaquin’s gales – simply because a watertight scuttle was left open. The cargo hold began to flood and damaged seawater piping failed, damning the ship and the 33 crew members onboard.

Image source (Indian Coast Guard)

Maersk Honam (2018)

If El Faro taught the industry anything, it was that seaworthiness should be a paramount concern to operators, shippers, and crew, but despite the disaster, the industry still averages at least one container ship fire every 60 days – a metric that would never be acceptable in aviation or rail transport. In the case of Maersk Honam, an Ultra Large Container Ship (ULCS), the stakes couldn’t have been higher.

After only a year of operation, the vessel caught fire in one of the cargo holds while the ship was headed west into the Arabian Sea, killing five crew and forcing the remainder to evacuate. The fire was so severe that the ship burned for five weeks before it could be extinguished.

How to Protect Your Assets Against Maritime Disasters

No matter the era, it’s always been true that weather, an act of God, and human error have contributed to an endless number of maritime disasters since man first set sail. Even with today’s modern technology, ever-increasing safety standards, and cutting-edge training, there’s no guarantee that your valuable cargo will arrive safely.

And because companies are shipping or sourcing overseas at an increasing rate, it’s more important than ever to protect your assets from the will of the ocean. Marine cargo insurance isn’t necessary when shipping goods, but having the added level of protection will certainly help you sleep at night – even if your cargo ends up sleeping at the bottom of the ocean.

![[Webinar] The Risks of International Shipping & How to Protect Yourself](https://traderiskguaranty.com/trgpeak/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022.07_ExplosiveShipping-TitleSlide-400x250.jpg)

![[Video] TRG Talks Trade Episode 1 – General Average on MSC Sabrina](https://traderiskguaranty.com/trgpeak/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/trg-talks-trade-ep01-FT-400x250.png)